As hard autumnal rain sweeps across the Rhondda valley, a thick grey mist hangs atop the mountain which towers over the village of Pentre. Amid the darkening early-evening gloom, there is the piercing glare of floodlights.

They belong to a football pitch, split into four sections to accommodate training sessions for groups from the Rhondda Cynon Taf Schools Football Association.

The children playing tonight are selected from 97 primary schools in the surrounding area. While they play, it can be tempting to wonder: ‘Could I be watching the next Jess Fishlock or Gareth Bale here?’.

Rather than players, however, you would be better served thinking which of these boys or girls might become leading coaches of the future.

This field, long before it was renovated with an all-weather playing surface, was home to promising young local footballers who are now some of Wales’ most successful managers.

Nottingham Forest head coach Steve Cooper and new Southampton boss Nathan Jones played here in the early 1990s, while former Wales manager Jayne Ludlow grew up nearby and took her first steps towards a stellar playing career with Arsenal at Treorchy Comprehensive School.

Even closer to Pentre Park, barely a goal-kick away, is the house where Jimmy Murphy lived. He was the last man to lead Wales to a World Cup back in 1958, and there is a blue plaque outside the house to mark his achievement.

Murphy remains the only person to have managed that feat – but that will change on Monday when Robert Page and his Wales side face the United States in Qatar.

Remarkably, Page is another product of this Rhondda football factory and, as he says himself, his valleys roots are an intrinsic part of the man he is today.

Page was born in Llwynypia, a village in the Rhondda valley, but that is not where he is from. That is Tylorstown, a different village nearby.

In the valleys, these distinctions matter.

“People think I’m from Llwynypia but that was just the hospital – there was no hospital in our valley. I was bred in Tylorstown,” Page explains.

“It’s in my DNA. I think it is with anybody who’s grown up in the valleys.

“Life wasn’t easy with the closures of the pits. A lot of the industry then was outside of the valleys so you were going further afield to put food on the table for your family.

“That’s when people rally around each other and help each other out. So from that aspect, I think I’ve been brought up in the right way and got good morals, and I’ve taken that throughout life with me.

“I have great memories. We created the Tylorstown Boys Club, which my dad was a part of and my mum used to wash the kit on the line every Sunday.

“We didn’t have a pitch in Tylorstown so the nearest pitch to us was Maerdy, the last village right at the top of the valley. That was interesting on a winter’s day! It was open and the rain would be driving down the valley, you could see it sideways.

“But you didn’t think of that, you just played because you love the game.”

Page stood out on the pitch during childhood, and not just because of his long – and now long gone – blonde hair.

A strong centre-back who also played up front occasionally, Page was selected to represent Rhondda Cynon Taf Schools.

“He was an exceptional character,” says Lynn James, who coached RCT Schools at the time and remains involved as a life member, proudly wearing one of the association’s white and red tracksuits as he reminisces on the touchline in Pentre.

“Physically, he was certainly a dominant individual and technically quite good as well, but what made him outstanding was his ability to take on information and take his techniques and turn them into skills.

“He was made captain and he was a good influence on others. He was mature and a leader, a quiet but humorous individual – exactly the kind of person you want as skipper.”

Page was soon attracting the interest of national selectors, though that presented some unusual challenges.

“When he was 14, he was nominated for a Welsh trial and we were all very confident having watched his performances in a recent county competition,” recalls Brian Hughes, an RCT Schools official since 1983 and, like James, a former teacher who continues to volunteer at training sessions several days a week.

“But when the trial details arrived, the date coincided with the day his sister was due to get married, which caused a bit of family stress. Luckily the trial was in Aberdare, 10am until 1pm, and the wedding was in Tylorstown, which was about 10 miles away.

“So I convinced the Welsh selectors that we could get him there, as long as he came off at 12 and I promised his parents he’d be back in time for the wedding.

“When the day came, I drove down to Tylorstown to pick him up and I can still remember his father putting the football kit in the boot and his mother putting the suit and tie and everything on the backseat.

“We got to Aberdare, he stood out in the trial, 12 o’clock came and I was like: ‘OK, you’ve obviously seen enough’. The chairman of selectors smiled and said: ‘Well, give him five more minutes’.

“At 12:10 I said he had to go, he had a quick shower, we drove over the mountain, stopped off at Maerdy, where my late mother lived and was on standby to sort the suit and buttonhole and everything.

“We then drove down to Tylorstown, I dropped him off outside the church, said goodbye and, as he was walking up the steps, I looked in the mirror and I could see the bride’s car pulling into the space I was vacating. So it was a very close call but a happy ending because he made the wedding and got selected for Wales.”

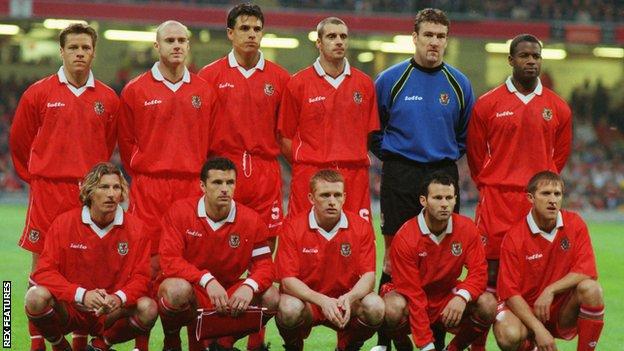

Page played in the same Wales schoolboy team as Robbie Savage and had already been spotted by Watford’s Welsh coach and scout Tom Walley, who helped launch the careers of compatriots Malcolm Allen and Iwan Roberts.

Before signing a full-time contract with Watford, however, a 15-year-old Page found time to play men’s football in the valleys.

“I played a couple of games for Ferndale Athletic and that was a real eye-opener,” he grins.

“So when I tell my young players to go out and do the hard yards, go out and play competitive football, there was nothing more competitive than playing for Ferndale Athletic. There were some tough boys in that league.

“But the biggest memory I have was the social afterwards, going to the pub and having a pint with all the boys. Of course mine was lemonade because I was not of an age to drink.

“I just loved the team spirit and the camaraderie. They loved playing football but they enjoyed the banter as much as well. That was incredible.”

Page cut his teeth as a young professional with Watford in the second tier, then known as the First Division, before their relegation to the Second Division in 1996.

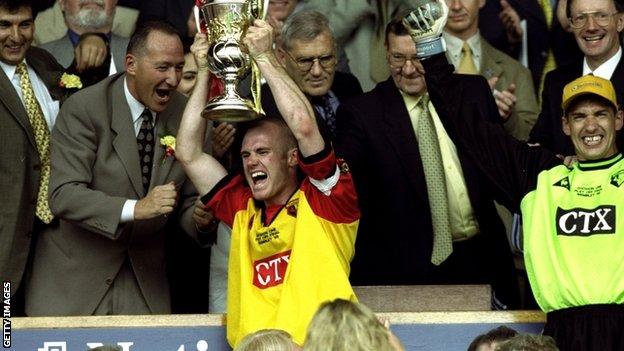

Watford’s manager at the time, the great Graham Taylor, recognised Page’s leadership qualities by appointing him captain at the start of the 1997-98 season when he was still only 22, and the centre-back vindicated that decision by leading the Hornets to the Second Division title.

A second successive promotion to the Premier League followed, with Page named Watford’s player of the season even as they were relegated in 2000.

Page joined Sheffield United a year later – and he still lives in the city with his family – but it is Watford, where he enjoyed the longest stay of his playing career, which had the most enduring effect on the man who would become Wales manager.

“I learned a lot from Graham Taylor. I thought he was first class. He had a real positive influence on my career,” says Page.

“He knew exactly when to get the boys on the grass, when to get them off it. So he would come in on a Monday morning, even after a defeat maybe, and think ‘They’ve had a long time on the grass, too much detail, we need to get them off it’.

“He’d get six volunteers to drive, we’d all be wondering what we’re doing, we’d all get in a car, drive for 20 minutes and end up in a lay-by somewhere.

“He’d be like ‘Right, follow me’ and we’d walk for an hour and end up in a country pub, where he’d already organised lunch for us and we’d sit, we’d have lunch and we’d have a little drink together.

“Then he’d say ‘Thanks, boys, see you tomorrow’ and it’d be the right thing to do at the right time.

“So knowing when to be intense, when to get them on the grass, knowing when to give them that little bit of a downtime.

“He was still having an influence on us because we were together as a group, getting to know each other more as friends and not on a footballing level.

“You learn a lot from all different managers you work with.”

Page will need a similar instinct in Qatar, where country pubs may not be as easy to find but where the demands of a World Cup will require a fine balance between serious work and the human need for an occasional light touch.

“They’re intense environments, as we saw in Baku [for last year’s European Championship] where the heat was quite severe as well,” says Page.

“So we know when to train them, when to work them, but we also know when the best time is to do a recovery [session] and when to just throw the lilos in the pool and get them to relax, and they don’t even realise they’re doing a recovery but just being in each other’s company. They’re getting those bonds as well.

“I think over the years it’s worked for us, and that stemmed back from Gary [Speed], who implemented the professionalism and different approach to the game and that elite level, and then Chris [Coleman] took it to another level.

“We’ve just inherited it and the big thing is we know when to relax and when to work hard.”

Page often cites the important roles his predecessors have played in getting Wales to this point, an unrivalled golden era in the nation’s footballing history.

After reaching the World Cup quarter-finals in 1958, Wales had to wait 58 years to qualify for their next major tournament and, at Euro 2016, Coleman’s side defied all expectations with an inspiring run to the semi-finals.

Every step of the way in France, the manager and his players would mention the late Speed, the legendary former captain turned coach who was in charge for less than a year but whose influence on his young squad – and on football in Wales as a whole – was profound.

He was succeeded by his close friend and former team-mate, Coleman, who built on Speed’s foundations to take Wales to new heights.

Another ex-colleague, Ryan Giggs, was next in line and, following his departure after Wales had qualified for Euro 2020, it was yet another of Speed’s former team-mates, Page, who assumed the responsibility for last year’s Covid-delayed competition.

Having been absent from football’s grandest stage for more than half a century, Wales have now qualified for three major tournaments out of four.

Two European Championships brought a glorious end to Wales’ barren years, though a long-awaited return to the World Cup will be on another level again.

Page is the man who has guided them there, following in the footsteps of another valley boy. In emulating Murphy, Page stands on the shoulders of a giant.

“Ultimately, your goal is to qualify for the World Cup. The fact that two valley boys have done it is incredible,” says Page.

“It’s literally a few miles over the hill and we’re both two managers from Wales who have got Wales to a World Cup.

“It’s a very proud moment and I’m pleased for Jimmy to get the recognition as well because it was some achievement back in those days.”

When Page revealed the 26 players Wales would be taking to the World Cup earlier this month, the location for the official squad announcement was symbolic: Tylorstown Welfare Hall.

A five-minute walk from his childhood home, this was the hub of the place where Page was raised, the heart of the community from which he was forged.

It was the natural setting for a celebration, not only of what the manager and his players have achieved but also a celebration of who they are.

It was meaningful because of its specificity to Page but also because it represented an essence; the kind of place that would feel familiar wherever you came from.

Sport is about more than what a group of people do on the field of play, it is about shared experiences, identity and a sense of belonging.

The Welsh language plays a prominent role in the culture around the country’s national team, and the Football Association of Wales has harnessed the power of one particular word in its preparations for the World Cup: hiraeth.

The word represents a deep longing for something, particularly one’s home, and it feels apt for a footballing nation where the majority of players and coaches live outside Wales and whose fanbase includes a widely scattered diaspora, many of whom will come together thousands of miles away in Qatar, all bound by a collective belief.

No matter how long you may have been away, there is always a place you can call home.

“Because I’m living outside of it [in Sheffield], I come back into it and then it hits me again,” says Page.

“It’s every time I come back. When I see my parents on a weekend, all these kids come up to me and ask me ‘Can you sign this? Can you sign that?’.

“It’s like ‘Wow, yeah, it’s real’ because sometimes I think it’s not sunk in properly. So just to have been a part of it is incredible, just an immense amount of pride.

“I took my kids to Cyprus for a week’s break and we landed in Paphos the same time as a flight from Cardiff, so my youngest lad asked me if I thought I’d be recognised and I said: ‘No, probably not’.

“But then one lad clocked me straight away with his family, then another and then another, and they all wanted photos.

“Everyone just wanted to say thanks and it was incredible, just to be a part of that is amazing.”

Life has changed for Page now he has steered Wales to a World Cup. Even as a Premier League footballer, Page could return home to visit his parents without much attention from strangers – but not anymore.

He has etched his name into Welsh football history and, alongside Murphy, his place in Rhondda folklore is even deeper-rooted.

And while Page will be in constant demand in Qatar, there will be one person who he will always make time for, his father Mal.

“With his health, not that there’s anything wrong with him, but it’d be too risky for him to fly all that way in the heat and so he probably won’t make it but he will be supporting,” says Page.

“He calls every day, apart from matchdays when he sends me a message but knows not to ring me because I’ll be busy – but as soon as I’m on the coach, he’s my first phone call.

“Straight away he is blunt! He says it as it is and that’s it, whether I want to hear it or not.

“But that’s him. I had a bit of a mouth apparently when I played and he used to shout at me from the touchline: ‘Zip it!’. He’d let me know if I did something he didn’t agree with.

“He’s no different now and that’s why I’ve got a lot of time for him.”