On the night before the opening game of baseball’s 1919 World Series, 46-year-old sportswriter Hugh Fullerton was worried. He suspected the series was going to be rigged.

The Cincinnati Reds were hosting the Chicago White Sox, and Fullerton was staying in the same hotel as legendary former pitcher Christy Mathewson. They talked about how they might be able to tell if a game was being fixed.

Mathewson explained the kinds of plays that could be indicative of something sinister – a misplaced throw to first base, or a pitch that was just slightly off-target.

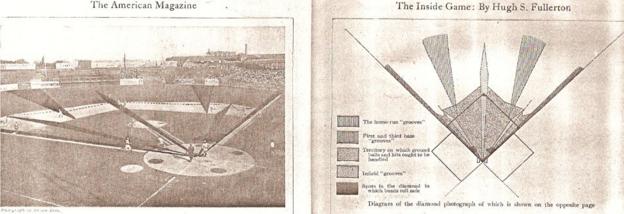

At the time there was no such thing as sports analytics – but Fullerton kept his own detailed shorthand notes and recorded plays during games. So they agreed to monitor and highlight all instances of anything questionable.

What followed was the Black Sox Scandal – which resulted in eight Chicago players being banned from Major League Baseball for life two years later, in 1921. Fullerton’s role was key.

Despite the opposition he faced during his lifetime, and baseball’s reluctance to face up to the dark influences often shaping its early fate, he was a radical pioneer whose impressive early advances helped set the foundation for data’s transformative effect on global sport.

When the centre-forward of your favourite football team looks up and takes a shot at goal they trigger a multitude of data points. The position of the player, the ball, team-mates and opponents will be collected, along with their speed, the movement of the ball, where the ball is struck, the time of the game, the state of the game and much more.

This event will be added to thousands collected in each match.

Football, like almost every other sport, has undergone a data revolution. And the conclusions drawn from analysis of that data has in turn transformed the way sport is played. For example in basketball, players of the modern era are far more likely to attempt three-point shots.

Much of this analytical explosion was triggered by the book, and film, Moneyball, which followed a new approach in baseball.

What is perhaps less well known is that a wide range of sports employed data collection systems and analysis going back to Victorian times. Baseball was one of those sports and one of the pioneers in this regard was Hugh S Fullerton.

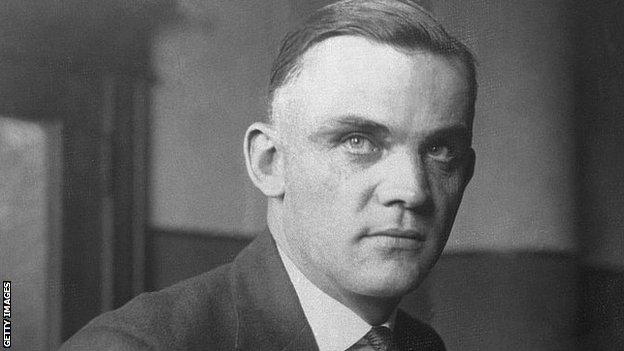

Born in Ohio in 1873, Fullerton fell in love with baseball at an early age and, although he reported on other issues and even dabbled in fiction, it was the thing he always came back to. He also loved numbers and collected detailed information on every game he attended, eventually more than 3,000.

Fullerton wanted to use the data he collected to find out how games were won and lost, not just to be added up for record keeping. He believed his scientific methods could predict a season’s worth of results based on mathematical values he assigned to players and positions.

Using the system he was able to make bold predictions about each year’s World Series.

In 1906, he leapt to prominence when he picked the ‘hitless wonders’ of the Chicago White Sox to beat the Chicago Cubs, despite the latter having won a record-setting 116 games during the regular season. He wrote that the Sox would win games one and three, the Cubs would win game two and that it would rain on the fourth day. He was spot on with each pronouncement.

In May 1910 he wrote an article for The American Magazine titled ‘The Science of Baseball’. It revealed some of his methods, alongside diagrams of theories and deductions. He was one of the first published writers to show the shorthand markings he used to denote batted balls, hits and pitches.

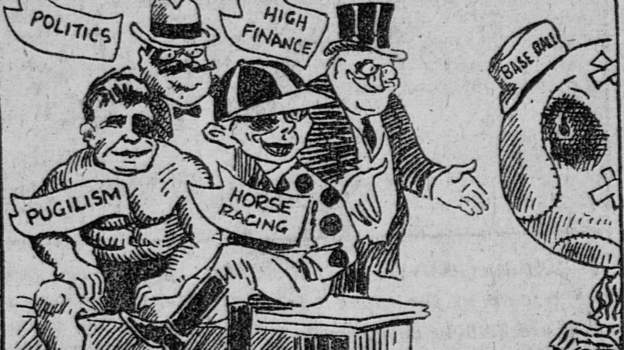

As more recent innovators have found, traditionalists didn’t like his new approach. A letter to Baseball Magazine complained that Fullerton “would have us believe that good ball can only be played by those men who work with the assistance of a tape-measure, a tee-square and an intimate knowledge of algebra and fractions”.

But using his data, Fullerton had correctly predicted the winners of the 1912, 1915, 1916 and 1917 World Series, often going against perceived wisdom, and including the exact numbers of games needed to win, using his self-devised ratings system.

So in 1919, when he gave his opinion on what was happening between the Cincinnati Reds and the Chicago White Sox, those words carried weight. And he was right.

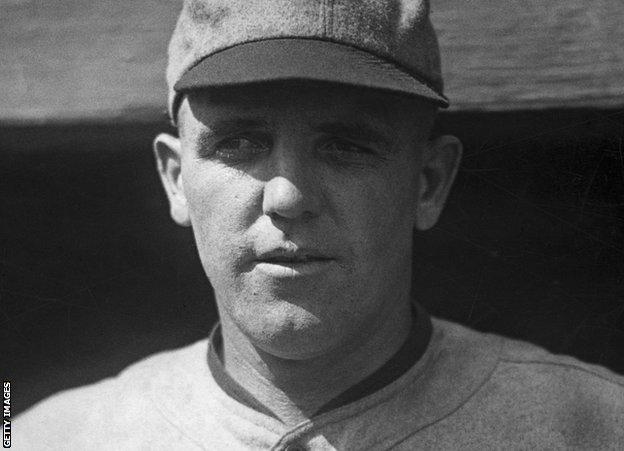

White Sox first baseman Chuck Gandil was the ringleader. He admitted as much in a Sports Illustrated interview, 37 years later.

He’d had discussions with gamblers in mid-September, weeks before the first match. The question of whether the World Series could be bought was answered – “yes, it could” – and by the end of the month he had a number of accomplices.

The key was star pitcher Eddie Cicotte, who Gandil knew had money troubles after buying a farm. Six others agreed to help, with varying degrees of apprehension.

A fee of $100,000 was agreed, to be shared among the eight conspirators. That would be worth about $1.6m today – not a lot compared to current MLB salaries, but Cicotte was then earning a yearly wage of $5,000.

There were rumours. By the time Fullerton had heard enough to become concerned, Gandil had taken delivery of a first cash payment. Cicotte went to bed that night and found $10,000 in cash under his hotel pillow. There was no going back for them now.

Meanwhile, Fullerton wired a message to all 40 of his syndicated newspapers: “Advise all not to bet on this series. Ugly rumours afloat.” The warning was widely dismissed and left unprinted. No-one would believe a World Series could be crooked.

Game one of the best-of-nine series – a new format – took place on a beautiful autumnal afternoon at Cincinatti’s Redland Field. Everyone involved in the conspiracy knew that White Sox pitcher Cicotte would give a clear signal that the fix was on: if he hit the first Reds batter it was happening.

His first pitch was called a strike, but the second hit Maurice Rath on the back. As he trotted to first base the money on the Reds kept building.

Before the match, the White Sox were seen as slight favourites, but Fullerton used his own methods to calculate they had a 71% chance of winning. Game one turned into a rout for the Reds: 9-1. Fullerton ringed three plays in dark pencil, each attributed to Cicotte.

After game two he circled six plays in another Reds victory. That night, White Sox catcher Ray Schalk complained to manager Bill Gleason that Cicotte was not pitching the way Schalk was asking. In the decisive fourth inning of game two he said the pitcher had “crossed” him four times, something he hadn’t done once during the rest of the season.

Cicotte was left out of game three – won by the White Sox 3-0 – but played again in game four. After the previous bust-up with Schalk he pitched as agreed. Instead he found other ways to sabotage the game.

Fullerton made two notes that highlighted what he saw as suspicious plays where Cicotte misfielded the ball and allowed the Reds to score two runs.

By the time of the eighth game the Reds led 4-3. Fullerton was frustrated. He had no concrete proof but was absolutely convinced the series was fixed.

He walked past a well-known gambler before the opening pitch and was advised to put some money on the Reds. “It’s going to be the biggest first inning you ever saw!” he was told. And it was. Claude Williams gave up four runs to the Reds as they built up a 10-1 lead before wining the game 10-5. The series was over.

Even with eight players conspiring it had been reasonably close. Fullerton believed his original prediction would have been proved correct without foul play.

He knew the numbers didn’t lie. The Sox players he suspected of being in on the fix committed nine errors during the series compared with only four by the rest of the squad combined. They gave up 21 runs compared to 14 by the non-fixers.

As the players cleared out their clubhouse and prepared to go their separate ways for the off-season, White Sox owner Charles Comiskey sent word that he had the pay cheques for the players under suspicion, and that they should come to his office to collect them. None of them did; they left the stadium without their money.

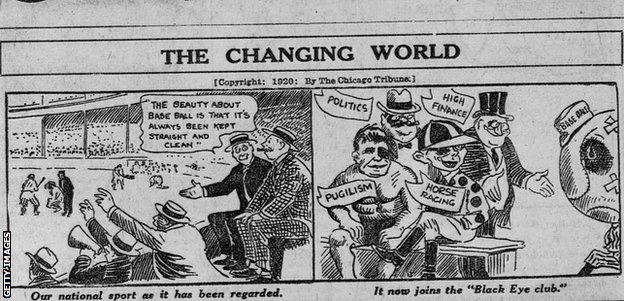

Dozens of newspapers covered the series and rumours abounded, but nobody wrote anything about a fix. When Fullerton prepared his post-series piece he couldn’t get it published. Both the Chicago Herald-Examiner and the Chicago Tribune backed down from printing the accusations for fear of being accused of libel.

Fullerton was frustrated. Not only did he place great faith in his scientific approach but he was a deeply moral man who felt compelled to speak out about wrong-doing, even if others felt it better to keep quiet ‘for the good of the game’. No-one else seemed interested in exposing what many suspected.

Furious, he set off into the wilderness on a fishing trip. When he returned to find still no action being taken he was even angrier.

Weeks later The Evening World in New York agreed to run his story, but it was edited down to be less inflammatory and finally published in December 1919. Rather than shaking the authorities into an investigation it made the author a pariah and he was accused of writing hogwash for personal gain and out of bitterness, because his prediction hadn’t come true.

Baseball Magazine, with the weight of the franchise owners behind it, called Fullerton “an erratic” who should “keep his mouth shut when in the presence of intelligent people”.

But even if Fullerton’s article didn’t immediately change anything, suspicions around baseball and gambling remained.

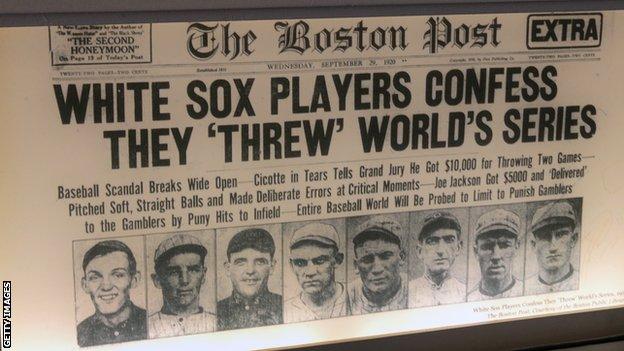

In September 1920 an investigation was opened into the possible fixing of a game between the Chicago Cubs and the Philadelphia Phillies. It was here that testimony claimed the 1919 series had been fixed and named several White Sox Players. Within days several had confessed.

In late June 1921, the trial of the State of Illinois versus Eddie Cicotte et al opened in Chicago.

It was revealed that three signed confessions had gone missing and the players faced up to five years in jail. Various conspiracy charges were levied and after a month of testimony the jury retired. They took three hours to return a clean sweep of not guilty verdicts.

However, the players’ joy was short-lived as the next day Judge Kennesaw Mountain Landis, the Commissioner of Baseball, issued a statement proclaiming that any player who knew about a potential fix and did not report it to his club would be banned from baseball for life, regardless of any court verdict.

The first players to fall foul of this announcement were the eight White Sox, now christened the Black Sox. None of them ever played Major League Baseball again.

Fullerton, disgusted by the whole affair, gradually stepped away from baseball reporting. The gains he had made in data analysis wouldn’t be more widely applied until 1947, when the Brooklyn Dodgers became the first team to hire their own statistician to advise on game strategy.

Fullerton died the same year. He was posthumously awarded the Taylor Spink Award by the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1964, finally receiving the recognition that had eluded him in life.

He’s now best remembered for helping to bring one of sport’s biggest scandals to the public eye and changing the way data is accepted into sports forever.

Rob Haywood’s book, Many Impossible Things: The Ingenious Evolution of Football Data, will be published in 2022.