Akara Etteh

Akara EttehEarly on a Saturday morning in April, Akara Etteh was checking his phone as he came out of Holborn tube station, in central London.

A moment later, it was in the hand of a thief on the back of an electric bike – Akara gave chase, but they got away.

He is just one victim of an estimated 78,000 “snatch thefts” in England and Wales in the year to March, a big increase on the previous 12 months.

The prosecution rate for this offence is very low – the police say they are targeting the criminals responsible but cannot “arrest their way out of the problem”. They also say manufacturers and tech firms have a bigger role to play.

Victims of the crime have been telling the BBC of the impact it has had on them – ranging from losing irreplaceable photos to having tens of thousands of pounds stolen.

And for Akara, like many other people who have their phone taken, there was another frustration: he was able to track where his device went, but was powerless to get it back.

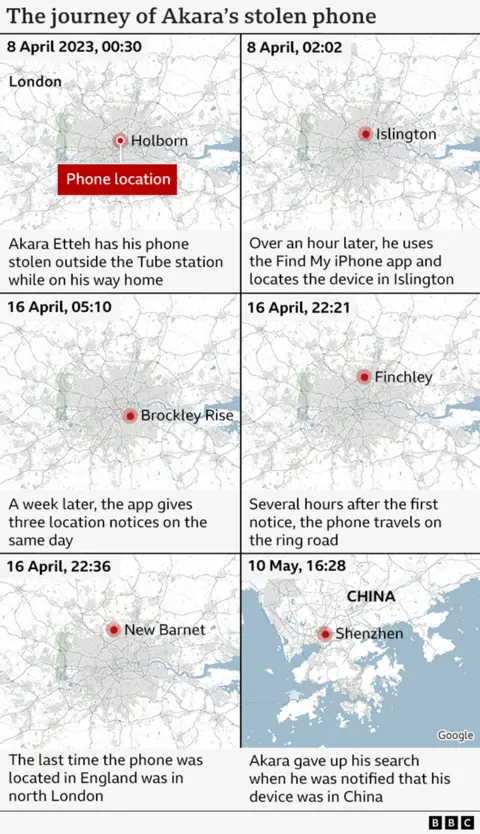

Phone pings around London

He put his iPhone 13 into lost mode when he got home an hour or so later – meaning the thieves couldn’t access its contents – and turned on the Find My iPhone feature using his laptop.

This allowed Akara to track his phone’s rough location and almost immediately he received a notification to say it was in Islington. Eight days later, the phone was pinging in different locations around north London again.

In a move he says he “wouldn’t recommend” with hindsight, he went to two of the locations his phone had been in to “look around”.

“It was pretty risky,” he said. “I was fuelled by adrenaline and anger.”

He didn’t speak to anyone, but he felt he was being watched and went home.

“I am really angry,” he said. “The phone is expensive. We work hard to earn that money, to be able to buy the handset, and someone else says ‘screw that’.”

Then, in May, just over a month after the theft, Akara checked Find My iPhone again – his prized possession was now on the other side of the world – in Shenzhen, China.

Akara gave up.

It is not uncommon for stolen phones to end up in Shenzhen – where if devices can’t be unlocked and used again, they are disassembled for parts.

The city is home to 17.6 million people and is a big tech hub, sometimes referred to as China’s Silicon Valley.

Police could not help

In the moments after Akara’s phone was stolen, he saw police officers on the street and he told them what had happened. Officers, he said, were aware of thieves doing a “loop of the area” to steal phones, and he was encouraged to report the offence online, which he did.

A few days later, he was told by the Metropolitan Police via email the case was closed as “it is unlikely that we will be able to identify those responsible”.

Akara subsequently submitted the pictures and information he had gathered from the locations where his stolen phone had been. The police acknowledged receipt but took no further action.

The Metropolitan Police had no comment to make on Akara’s specific case, but said it was “targeting resources to hotspot areas, such as Westminster, Lambeth and Newham, with increased patrols and plain clothes officers which deter criminals and make officers more visibly available to members of the community”.

Lost photos of mum

Many other people have contacted the BBC with their experiences of having their phones taken. One, James O’Sullivan, 44, from Surrey, says he lost more than £25,000 when thieves used his stolen device’s Apple Pay service.

Meanwhile, Katie Ashworth, from Newcastle, explained her phone was snatched in a park along with her watch, and a debit card in the phone case.

“The saddest thing was that the phone contained the last photos I had of my mum on a walk before she got too unwell to really do anything – I would do anything to get those photos back,” the 36-year-old says.

Again, she says, there was a lack of action from the police.

“The police never even followed it up with me, despite my bank transactions showing exactly where the thieves went,” she said.

“The police just told me to check Facebook Marketplace and local second-hand shops like Cex.”

‘Battle against the clock’ for police

So why are the police seemingly unable to combat this offence – or recover stolen devices?

PC Mat Evans, who has led a team working on this kind of crime for over a decade within West Midlands Police, admitted that only “quite a low number” of phones that are stolen actually get recovered.

He says the problem is the speed with which criminals move.

“Phones will be offloaded to known fences within a couple of hours,” he said.

“It’s always a battle against the clock immediately following any of these crimes, but people should always report these things to the police, because if we don’t know that these crimes are taking place, we can’t investigate them.”

And sometimes just one arrest can make a difference.

“When we do catch these criminals, either in the act or after the fact, our crime rates tank,” he said.

“Quite often that individual has been responsible for a huge swathe of crime.”

But the problem is not just about policing.

In a statement, Commander Richard Smith from the National Police Chiefs’ Council, which brings together senior officers to help develop policing strategy, said it would “continue to target” the most prolific criminals.

“We know that we cannot arrest our way out of this problem,” he said.

“Manufacturers and the tech industry have an important role in reducing opportunities for criminals to benefit from the resale of stolen handsets.”

Tracking and disabling

PC Mat Evans

PC Mat EvansStolen phones can already be tracked and have their data erased through services such as “Find My iPhone” and “Find My Device”, from Android.

But policing minister Dame Diana Johnson said this week the government wanted manufacturers to ensure that any stolen phone could be permanently disabled to prevent it being sold second-hand.

Police chiefs will also be tasked with gathering more intelligence on who is stealing phones and where stolen devices end up.

A growing demand for second-hand phones, both in the UK and abroad, is believed to be a major driver behind the recent rise in thefts, the government said.

The Home Office is to host a summit at which tech companies and phone manufacturers will be asked to consider innovations that could help stop phones being traded illegally.

PC Evans said there was “no magic bullet”, but he said there was one thing manufacturers could do which would be “enormously helpful” to the police – more accurate tracking.

“At this moment in time, phone tracking is okay,” he said.

“But it’s not that scene in Total Recall yet, where you’re able to run around with a tracking device in your hand, sprinting down the road after a little bleeping dot.

“I appreciate it’s a big ask from the phone companies to make that a thing, but that would be enormously helpful from a policing perspective.”

Apple and Android did not provide the BBC with a statement, but Samsung said it was “working closely with key stakeholders and authorities on the issue of mobile phone theft and related crimes”.

Additional reporting by Tom Singleton