Outside Havana’s Hotel Nacional, the city is jubilant: this Spanish-founded port is in the midst of celebrating its 500th anniversary. Vintage Bel-Airs and Buick convertibles ply the roads, painted in gumdrop colours. Fireworks and canon fire fill the midnight sky, and music pulses in the bars lining Obispo Street. Along Calle Galiano, bridged by nets of white and blue LEDs evoking stellar constellations, locals are dancing and drinking rum. On the border of Habana Vieja, Old Havana, the dome of the newly restored Capitol gleams like a polished helmet.

Seven flights below me, in the plaza visible from my window, a bandstand floats in an island of floodlights. By midnight 100,000 people will fill that square, dancing to a free quincentennial anniversary concert.

Five flights down, meanwhile, on the Nacional’s mezzanine, is the hotel’s business centre. Its frosted glass doors are stencilled with jazzy gold letters: INTERNET. And as its old desktop computers remind me, I’m here to celebrate an anniversary as well.

I accomplished a minor miracle: I uploaded the first travel blog posts ever published on the World Wide Web

Twenty-five years ago, at the dawn of the internet era, I set off to travel around the world – from Oakland, California, to Oakland, California – without stepping on an airplane. Along the way, I accomplished a minor miracle: I uploaded the first travel blog posts ever published on the World Wide Web.

You may also be interested in:

• Fidel Castro’s secret love affair with NYC

• A journey to the Disappointment Islands

• Is Havana getting a makeover?

Cuba feels like an appropriate place to ring in this milestone. The country is one of the least internet-friendly places on the planet, with fewer than 40% of its citizens having access to the Web amid strict government censorship. But even this is a dramatic contrast to 1994, when the words “World Wide Web” drew puzzled glances from almost everyone I met on my round-the-world journey. Still, Cuba’s relative isolation from the global addiction to netsurfing reminds me of those pioneering days.

But unlike my four previous visits to the island, I won’t need the hotel’s desktop dinosaurs hibernating in its business centre. As a paying guest of the Nacional, I have been provided with a tongue-twisting username and password which allow me, when the stars align, to get online from the comfort of my room.

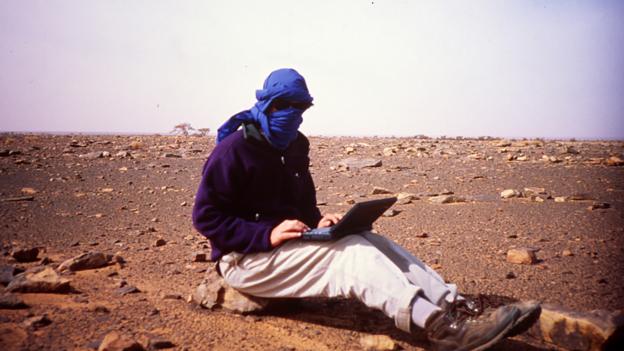

Back in 1993 and 1994, in the course of my nine-month global odyssey, I was a man with a mission. O’Reilly Media, a well-known publisher of data science guides, had asked me to send back real-time stories from various stops along my journey. During that trip, I carried one of the first (maybe the very first) ultra-portable laptops. Made by Hewlett-Packard, the OmniBook 300 was a small, superlight marvel that ran on AA batteries as well as AC. It had an adorable pop-out mouse, and a built-in modem.

O’Reilly (one of the first companies ever to have an online presence) had created a website called the Global Network Navigator. It planned to post my dispatches on its site under the name “Big World,” linking each story to its location on a world map. Click on the country, and you’d see the story. Today, a chimpanzee could build the page, but in 1994, it was a watershed. Mosaic, the browser that popularised the World Wide Web and made it user-friendly, had been launched only months before my departure.

Back in those days, you could count the number of sites on the Web

The internet was the Wild West; I could have bought “pizza.com” for $20. No-one had ever posted internet-based travel diaries before. Back in those days, you could count the number of sites on the Web (a roster that included The Exploratorium, Doctor Fun, and Chabad). But there was no such thing as a travel “blog” – the term “weblog” wouldn’t be coined for another four years.

So off I went, into a world where even email was still a novelty. Writing on the OmniBook was easy. The hard part came when I tried to send my dispatches home from far-flung places like Dakar and Lhasa. My first story, sent from Oaxaca on 6 January 1994, was called One Hundred Nanoseconds of Solitude. The process of transmitting it back to Big World took two days, during which I haunted the city’s central telecommunications office and babbled to its technicians (I spoke no Spanish), finally finding someone who figured out how to send my 2,500-word dispatch, sans photos, through the phone lines to California.

A quarter century later, there would be more than half a billion blogs on the Web

The process of finding internet connections reliable enough around the world to upload each of the 20 dispatches I ultimately posted was maddening. But it was also deeply immersive. In 1994, sending out a blog was an adventure: it essentially forced me to interact with people I wouldn’t seek out during a normal trip. In my scattered ports of call, I befriended local telecom managers (Turkey), diplomats (China), computer nerds (Kathmandu), even ship captains (the Ursus Delmas, while crossing the Atlantic). All of them were amused by what I was doing. The idea of posting travel stories on the Web was utterly new, and few people thought it would catch on – but everyone saw the potential if it did.

Everyone, I guess, but me. Little did I know as I sat sipping Mexican hot chocolate with the head of Oaxaca’s data services branch as my first post uploaded, that a quarter century later, there would be more than half a billion blogs on the Web – with hundreds of thousands focusing on travel alone.

Somehow, I missed that particular boat (though I did find a freighter to carry me home from Hong Kong back to Oakland). Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, I continued publishing dispatches for various online magazines. But it never occurred to me to position myself as a professional blogger. I never thought to “brand” myself or even make much of a fuss about my relatively small, though pioneering, e-footprint. By the time 2010 came around, I rarely wrote travel blogs at all. Meanwhile, the ripples from the pebble I’d tossed into the World Wide Web have grown into a tsunami, with some travel bloggers (and their mobile disciples, Instagram influencers) making small fortunes.

As I grabbed a Coke (one of the very few American brands you’ll see in Cuba) from my mini-suite’s minibar and mixed it up with some Havana Club, I wondered: Why did I stop? I think it has to do with the reason I’ve been inspired to travel in the first place. It’s not just about immersion; it’s also about disruption.

Years ago, when I was living part-time in Kathmandu, boarding the plane from San Francisco to Nepal was a total release. Whatever was left undone or overlooked – whoever I’d forgotten to connect with before hoofing my backpack down those economy-class aisles – was now part of the past. Every trip was a chance to challenge myself anew and confront an unfamiliarity that both shattered and expanded my world view. It was a way to reinvent my life, and thrust myself out of my comfort zone.

In 1994, the goose chase of finding connectivity and filing digital dispatches was an exotic exercise. It made me reliant on tech-savvy locals, whether in Senegal or Shanghai. By the turn of the millennium, though, blogging had become more about isolating yourself in an internet cafe, and paying by the minute. I did it when necessary, but it no longer felt like an immersive or disruptive exercise. What had once been an expedition became a commute.

What had once been an expedition became a commute.

Don’t get me wrong. This isn’t about a “right” or “wrong” way to travel. Though I’ve often fretted about the post-2000, trade-off between immersion and connectivity, I know they’re not mutually exclusive. Like everything else in life, it’s a matter of balancing priorities. When I read back over my Israel dispatches from 2004, or even my Cuba blogs from 2011, they’re as immersive as anything I’ve ever written.

But from where I sit at this moment – in my room overlooking the crowded Malécon, with the Latin songo rhythms of Havana shaking my windows – I realise that writing this dispatch, and trying to upload it on the Nacional’s fickle WiFi, is not a disruption. It’s a distraction. Where I really want to be, at this moment, is immersed in the chaos outside.

So, I’m gonna log off now, and get down there. Because a quarter century after I uploaded those primordial Big World dispatches, we’re living on a much smaller planet – a place where, for me at least, disconnection is the new disruption.

Travel Journeys is a BBC Travel series exploring travellers’ inner journeys of transformation and growth as they experience the world.

Join more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called “The Essential List”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.