Antonio Esfandiari’s heart was beating like a drum. There was $18m (£15.8m) on the line, the cash was stacked up about 12ft from where he was sitting.

It was 3 July 2012 and Esfandiari, then 33, had outlasted 47 other poker players in Las Vegas. Either he or Englishman Sam Trickett would be claiming the biggest first prize in the game’s history to date.

The live TV cameras were primed, the tension among fans at breaking point. The commentators held their breath as the dealer prepared to reveal the final card. Esfandiari was about to experience the most euphoric moment of his life. But he still looked like the coolest head in the room.

When he was confirmed as the winner, he immediately took off his glasses. Not in relief or disbelief but to save them from being crushed as his family and friends flooded in from all sides to congratulate him.

The celebrations were wild. He was held high in the air by the group now gathered tight around him. Somebody threw over a huge bundle of $100 bills from the stack. Eventually he got his glasses back on.

As the huddle cleared and broadcaster ESPN kept rolling, everybody recognised something extraordinary had just happened.

For Esfandiari it represented the culmination of a career which began in very different circumstances a decade earlier.

But Poker itself had changed immeasurably in that time too. A once frowned-upon card game now had its own share of the United States’ sporting mainstream thanks to a boom in popularity that was perhaps reaching a peak.

This is the story of how it got there.

In 1999, TV producer Steve Lipscomb was working on a one-hour documentary titled: ‘On the Inside of The World Series of Poker.’

He’d also read an article in the New York Times that said 20 million Americans were playing poker every week.

The article, coupled with the success of his show when it was released, led Lipscomb to believe there was a giant, untapped market for the game.

So he founded the World Poker Tour (WPT).

“My business plan was: ‘If we’re as successful as bowling or billiards we’ll break even,'” he says now.

“On the other hand, if we end up like the NBA or the NFL, then this is an extraordinary opportunity.”

The WPT wasn’t the only player at the table. The World Series of Poker (WSOP) had been around since the 1970s, but until the early 2000s existed almost in isolation. You had to go looking for it. It was hardly ever on TV.

By the end of the WPT’s first televised season, running from June 2002 to April 2003, its peak of 2.2m concurrent viewers was higher than an average NBA game at the time, according to Lipscomb.

“We blew the doors off,” he says.

“We started raising so much money we didn’t have to pitch to the TV networks – they eventually came to us. All of these other sporting networks like ESPN and NBC jumped in because they wanted a piece of the pie.

“Whether they thought it was a sport or not was really irrelevant, because all of their audience thought it was a sport.”

Not everyone will agree in that debate, but Lipscomb’s influence was certainly making poker look like a sport. That was a key part of the plan: to take a card game and shape a familiar televised format around it.

Each WPT show would have two commentators, one calling the action and another taking a more analytical approach. They were filmed with fans in attendance, giving it that live-sport feel. Innovations included a camera fitted under tables to show each player’s hand.

A bigger problem was fitting all the key information on screen.

“It took us eight months to get it right,” Lipscomb says.

“We had to build tools that would take cards off the screen when somebody folds. When we did it, it was a dance-in-the-halls moment.

“Now you could be in a bar with the TV on mute, look at the screen, and the graphics would tell you everything that was happening. That’s when I believe something truly becomes a televised sport.

“I told people we could do this, we could make poker into a sport.”

At the same time, the more prestigious and historically respected World Series of Poker (WSOP) was expanding too. Poker coverage had always been limited but, now carefully packaged for prime time TV, it was gleefully unwrapped by the American public.

“Within months of our shows going on air everything transformed,” Lipscomb continues.

“We thought of televised poker as a five-act Shakespearean play where everybody but one person dies along the way. We made villains and heroes out of everybody at the table.

“If you asked anyone in 2001 if they knew any professional poker players, they wouldn’t. But after the first season of the WPT, the players on those final tables, they were rock stars, man.”

One of those ‘rock stars’ was Esfandiari.

Born in Tehran in 1978, Esfandiari’s family moved to the United States when he was eight. The Iran-Iraq war of 1980-88 played a big role in their decision to leave.

Growing up in the US was a tough transition. He says there was a lot of hostility and racism towards Iranians at the time, partly because of the hostage crisis that began at the US embassy in Tehran in 1979, with 52 American diplomats and citizens held for 444 days.

During those difficult early years, Esfandiari was introduced to the game that would ultimately shape his life.

“My dad and his friends used to play poker when I was a kid, but an Iranian version of poker,” he says.

“I would always sneak in and try and stay up past my bed time, I thought it was awesome.”

By age 19 Esfandiari was playing no-limit Texas hold ’em at his local casino. Having gained a fake ID (many US states require players be over 21) and digested a strategy book on poker, a whole new world was opening up.

“I saw the truth right there at the table, I couldn’t believe it,” he says. “I was like ‘wow, nobody can spell poker here, never mind play it’. It was unbelievable how bad people were. And because of the book I’d read, I was able to earn a bit of money.”

The more Esfandiari played, the more he earned. Soon he started to make more money from poker than from his part-time job as a magician.

But attitudes towards the game were often negative. Many people treated those who played it with suspicion.

Esfandiari says: “My friend Phil Laak and I, we used to roam around looking for games. But obviously we would have nights where we would not play poker and we would go out instead.

“On those nights if we ever met any women, back in our single days, they would say ‘what do you do?’ When we’d tell them, they wouldn’t want anything to do with us.”

According to Esfandiari, the WPT “single-handedly” and “without a doubt” played the biggest role in changing poker’s reputation.

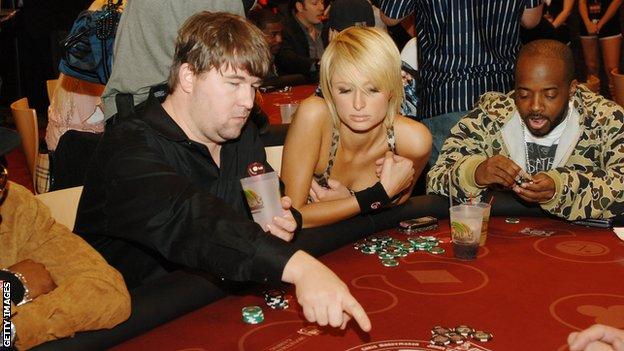

“All of a sudden poker exploded on TV, you had all these celebrities playing and it became a cool thing,” he says. “It was no longer looked down on.”

A number of factors fused together to form the power behind poker’s increase in popularity around this time, known as the ‘Poker Boom’.

Movies such as Rounders (1998) starring Edward Norton and Matt Damon brought the game to a wider audience. The growth of the internet spawned online play, making it more accessible worldwide than it had ever been before.

And an accountant named Chris Moneymaker won the 2003 WSOP main event, pocketing $2.5m (£2.19m) after qualifying online. It inspired amateur players across the planet; in 2003 there had been 839 entrants, in 2006 there were 8,773 – a record that still stands.

A game once maligned by the general public was being broadcast and making headlines around the globe, beyond poker circles.

And the prize money on offer was going through the roof.

Esfandiari appeared in the WPT’s debut season from 2002-2003, but it wasn’t until season two that he started to gain recognition.

In February 2004 he outlasted 381 other players to win a $1.4m (£1.22m) first prize. Fans took pictures with him, they wanted his autograph and began to follow him as they would a favourite sports team.

“For a kid who was pretty insecure growing up and going through the things I had to experience, it was extremely validating,” says Esfandiari, who was 25 at the time.

“People would come up to me and say: ‘I love to watch you play, I tune in to watch you play.'”

The $18m win of 2012 was at a WSOP event – the Big One for One Drop, which helped raise a reported $5m (£4.38m) for a water charity. It remained a record prize until Bryn Kenney of the US won $20.5m (£17.99m) at the Triton Million of 2019.

Esfandiari describes it as “the ultimate, most euphoric out-of-body experience of my life”.

“Because it wasn’t just me,” he adds. “My entire family, my friends, my whole world and everybody in it was up. Financially, socially, everything.

“The whole world was watching. Newspapers in France, Israel, Germany and all over the place were writing that somebody had won $18m (£15.7m) playing poker.

“With all the experiences I’ve had in my life, none of them compare to that first minute after realising I had won that tournament.”

Esfandiari, now 43, lives with his wife and children in Venice Beach, California. He says the poker scene has “completely changed” since the early 2000s.

“Back then poker was so fresh that if you won one event you were an instant star,” he says. “Fast forward to today, you can win four and nobody knows you.”

He believes the standard has also improved – “there are no bad players left” – owing partly to “the internet and the vast knowledge available, all the training videos”.

He also believes it isn’t as interesting. Esfandiari and others have been critical of some newer players adopting the Game Theory Optimum approach, which heavily draws on mathematics in its strategy. Those who favour it have been accused of lacking charisma and innovation – two of the key elements that helped grow poker’s popularity on TV.

That there are players like Esfandiari, players who have enjoyed consistent success over a number of years, supports the case that poker requires skill and strategy. But nonetheless the game always comes with big risks – such as that of problem gambling.

A 2018 study published in Australia found 39% of the regular poker players it surveyed had moderate to severe gambling problems, while around a quarter had caused financial problems for themselves or their households.

Lipscomb, who sold his stake in the WPT in 2009, says they would “spend time making sure, particularly in tournament poker, that you can only pay a certain amount and it’s all you can lose”.

He also believes problem gamblers are less likely to be found among professional poker players.

One recent case exposes the limitations behind that argument.

Dennis Blieden, a former WPT champion, was sentenced to six and a half years in prison in June 2021 for embezzling $22m (£19.3m) from his employer StyleHaul, a media agency, where he was in charge of accounts.

In a letter to the judge, Blieden, 31, outlined how his gambling addiction had started at a young age, before worsening in line with his poker career.

He described how he “idolised” the stars of the ‘poker boom’ and became “obsessed” with matching their achievements.

With stolen funds he entered high-stakes competition and won $1m (£8.77m) in the LA Poker Classic of 2018. The “validation” that brought was “no doubt an accelerant in my gambling”, he wrote, adding: “I did everything I could to keep that reputation alive.”

Esfandiari recalls a time when as a younger man he worried he might have a gambling addiction. But over 20 years on he says “professional players don’t see poker as gambling, it’s a calculated risk”.

He adds: “For about a month and a half when I was 21, I was playing poker every single day. I was waiting tables, player poker, waiting tables, playing poker, and I realised it was too much.

“I realised I didn’t want to end up as someone spending their whole life in the casino, losing all their money, even though I was actually winning. So I decided to tone it down.

“But when you sit down to play roulette, craps or blackjack, any of those sort games, you’re against the casino. Every time you bet $100, you’re losing two, three, four five bucks mathematically

“Poker players on the other hand, we believe we are the casino when we sit down.

“When you play poker against good players and you’re a bad player, you’re going to lose money against the good player. It might not be that day, but by the end of the year the pro will take the money.

“You have to put in the work. You can’t just show up and think you’re going to beat the best.”