Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere are strong indications that the US and UK are poised to lift their restrictions within days on Ukraine using long-range missiles against targets inside Russia.

Ukraine already has supplies of these missiles, but is restricted to firing them at targets inside its own borders. Kyiv has been pleading for weeks for these restrictions to be lifted so it can fire on targets inside Russia.

So why the reluctance by the West and what difference could these missiles make to the war?

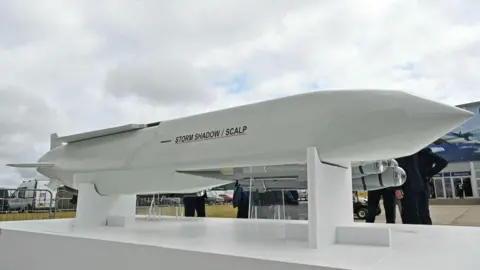

What is Storm Shadow?

Storm Shadow is an Anglo-French cruise missile with a maximum range of around 250km (155 miles). The French call it Scalp.

Britain and France have already sent these missiles to Ukraine – but with the caveat that Kyiv can only fire them at targets inside its own borders.

It is launched from aircraft then flies at close to the speed of sound, hugging the terrain, before dropping down and detonating its high explosive warhead.

Storm Shadow is considered an ideal weapon for penetrating hardened bunkers and ammunition stores, such as those used by Russia in its war against Ukraine.

But each missile costs nearly US$1 million (£767,000), so they tend to be launched as part of a carefully planned flurry of much cheaper drones, sent ahead to confuse and exhaust the enemy’s air defences, just as Russia does to Ukraine.

They have been used with great effect, hitting Russia’s Black Sea naval headquarters at Sevastopol and making the whole of Crimea unsafe for the Russian navy.

Justin Crump, a military analyst, former British Army officer and CEO of the Sibylline consultancy, says Storm Shadow has been a highly effective weapon for Ukraine, striking precisely against well protected targets in occupied territory.

“It’s no surprise that Kyiv has lobbied for its use inside Russia, particularly to target airfields being used to mount the glide bomb attacks that have recently hindered Ukrainian front-line efforts,” he says.

Why does Ukraine want it now?

Ukraine’s cities and front lines are under daily bombardment from Russia.

Many of the missiles and glide bombs that wreak devastation on military positions, blocks of flats and hospitals are launched by Russian aircraft far within Russia itself.

Kyiv complains that not being allowed to hit the bases these attacks are launched from is akin to making it fight this war with one arm tied behind its back.

At the Globsec security forum I attended in Prague this month, it was even suggested that Russian military airbases were better protected than Ukrainian civilians getting hit because of the restrictions.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesUkraine does have its own, innovative and effective long-range drone programme.

At times, these drone strikes have caught the Russians off guard and reached hundreds of kilometres inside Russia.

But they can only carry a small payload and most get detected and intercepted.

Kyiv argues that in order to push back the Russian air strikes, it needs long-range missiles, including Storm Shadow and comparable systems including American ATACMs, which have an even greater range of 300km.

What difference could Storm Shadow make?

Some, but it may be a case of too little too late. Kyiv has been asking to use long-range Western missiles inside Russia for so long now that Moscow has already taken precautions for the eventuality of the restrictions being lifted.

It has moved bombers, missiles and some of the infrastructure that maintains them further back, away from the border with Ukraine and beyond the range of Storm Shadow.

The Institute for the Study of War think tank (ISW) has identified around 200 Russian bases that would be in range of Storm Shadows fired from Ukraine. Some further additional bases would come into range if the US approves the use of ATACMS missiles in Russia.

But one ex-US official told the BBC that there was scepticism in the White House and the Pentagon about how much difference using Storm Shadow missiles inside Russia would make to Ukraine’s war effort.

Justin Crump of Sibylline says while Russian air defence has evolved to counter the threat of Storm Shadow within Ukraine, this task will be much harder given the scope of Moscow’s territory that could now be exposed to attack.

“This will make military logistics, command and control, and air support harder to deliver, and even if Russian aircraft pull back further from Ukraine’s frontiers to avoid the missile threat they will still suffer an increase in the time and costs per sortie to the front line.”

Matthew Savill, director of military science at Rusi think tank, believes lifting restrictions would offer two main benefits to Ukraine.

Firstly, it might “unlock” another system, the ATACMs.

Secondly, it would pose a dilemma for Russia as to where to position those precious air defences, something he says could make it easier for Ukraine’s drones to get through.

Ultimately though, says Savill, Storm Shadow is unlikely to turn the tide. Ukraine doesn’t have many missiles, and the UK has very few left to give.

And it has been widely reported that, in anticipation of this permission being given, Moscow has already moved the bulk of its air assets and ammunition deeper into Russia, beyond the range of Ukraine’s missiles.

Why has the West hesitated?

In a word: escalation.

Washington worries that although so far all of President Vladimir Putin’s threatened red lines have turned out to be empty bluffs, allowing Ukraine to hit targets deep inside Russia with Western-supplied missiles could just push him over the edge into retaliating.

The fear in the White House is that hardliners in the Kremlin could insist this retaliation takes the form of attacking transit points for missiles on their way to Ukraine, such as an airbase in Poland.

EPA

EPAIf that were to happen, Nato’s Article 5 could be invoked, meaning the alliance would be at war with Russia.

Ever since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, the White House’s aim has been to give Kyiv as much support as possible without getting dragged into direct conflict with Moscow, something that would risk being a precursor to the unthinkable: a catastrophic nuclear exchange.

Nonetheless, it has allowed Ukraine to use Western supplied missiles against targets in Crimea and the four partially occupied regions that Russia illegally annexed in 2022. While Moscow considers these regions part of its territory, the claims are not recognised by the US or internationally.

Putin’s claims of Western involvement

One reason President Putin views the use of Storm Shadow as a direct intervention in the war by the US and UK is his belief that Ukrainian troops cannot use long-range missiles systems without the aid of Western specialists.

He told reporters in Russia that “only servicemen of Nato countries can input flight missions into these missile systems,” adding that Kyiv also relies on satellite intelligence supplied by the West to choose targets.

Manufacturer MBDA declined to comment on the claims when approached by the BBC, directing queries to the UK Ministry of Defence.

A spokesperson for Ukraine’s presidential office also declined to address Putin’s allegations, saying they could not comment on “special technical details regarding weapons”.

Justin Crump cast doubt on Putin’s claim, telling the BBC that if “that claim were true, then Russia would have made it more clearly when the weapons were first supplied, and when they conducted successful and impactful operations against for example the Black Sea Fleet HQ in occupied Crimea”.

“The missile is available for export sales; is Russia seriously saying that any buyer would have to have a Nato/UK team to program and use the missile? That must presumably be buried deep in the fine print of the brochure, and wouldn’t make it an appealing prospect,” he noted.