Sign up for notifications to the latest Insight features via the BBC Sport app and find the most recent in the series here .

On a cold, crisp February evening under the cover of darkness, a woman stealthily creeps towards Wimbledon’s empty grandstands and pristine grass courts.

She climbs the hedge, carrying in her bag five tins of paraffin oil, a bundle of firelighters, a package of wood shavings and two boxes of matches.

She picks her spot, places her bag on the court and readies the ingredients – preparing to decimate one of Britain’s most famous sporting venues.

It is just one incident in a year of protests at major sporting events; the latest attempt to win hearts and minds on an issue that divides the country and provokes anger on both sides of the argument.

But the year in question is 1913.

There is one final item in the woman’s bag – a piece of paper. On it is written ‘No peace until women get the vote’.

“The suffragettes are the largest domestic terror organisation who ever operated on British soil, they have no equivalent,” says historian Dr Fern Riddell.

“They were on another scale to anything else. There were hundreds and hundreds of attacks, with hundreds of people in prison and nobody ever talks about that fact.”

Their cause is better remembered than the methods through which it was pursued.

In the early part of the 1800s, the thought of women having the right to vote in the United Kingdom was completely alien to many.

In 1831, only a tiny part of British society – around 4,500 property-owning men or 0.2% of the total population – could take part in parliamentary elections.

The following year, the Reform Act extended the vote to more men, but explicitly barred women from the polling booth.

By the early 20th century, after 60 years of peaceful protests, handing out pamphlets and making polite requests to government to give women the right to vote, many members of women’s suffrage movements were growing tired and frustrated.

“There were lots of people who didn’t support suffrage – suffrage is a very complicated idea for a lot of people, as bizarre as that may seem today,” said Dr Riddell, author of Death in Ten Minutes, a biography of suffragette bomber Kitty Marion.

“The idea of women having the vote was not hugely supported.”

The suffragettes decided they needed to up the ante.

When people think of the suffragettes, they likely think of marches and protests with banners, large gatherings with leaders of the movement delivering speeches to rousing crowds, or women tying themselves to railings and refusing to move.

And until around 1909, that is what the suffragettes did.

But change was coming to the movement. The Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) began in 1903, led by Emmeline Pankhurst. Its motto was “deeds not words” and quickly it found, having exhausted other routes, that violence was most persuasive.

Between 1912-1914 the suffragettes were the largest threat to domestic peace in the country, with cells across the country.

They carried out hundreds of attacks aimed at causing as much destruction and disruption as possible to everyday life.

Pankhurst said the WSPU’s aim was “to make England and every department of English life insecure and unsafe” by creating a “reign of terror”.

By the end of 1912, 240 people had been sent to prison for militant suffragette activities.

Direct action took the form of bombing MP’s houses, placing explosives in post boxes and carrying out arson attacks on public places, such as trains and churches.

Targets were carefully selected based on their significance to British life, so it is no coincidence that some of the suffragettes’ favoured marks were also sporting venues.

“Sport is a huge part of English cultural life, if you’re going to target things to bring your cause to ordinary people, of course you’re going to target sport,” says Dr Riddell.

Golf and racecourses took the brunt of the attacks because they were frequently empty, largely unguarded and, along with other sports premises, were predominantly male-dominated arenas.

Golf club members often turned up for a morning round only to discover that intruders had spent the night hacking up turf, throwing acid around the greens and carving the letters VW or Votes for Women into the ground.

A fire at Ayr racecourse caused £2,000 of damage while Hurst Park racecourse was burned down by Marion, a prominent member of what became known as the ‘young hot bloods’ – a segment of the WSPU carrying out violent, direct action.

Grandstands were a popular target for arson attacks, they were large and the spectacle of one ablaze was certain to attract publicity.

A plot to burn down the Crystal Palace grandstand on the eve of the 1913 FA Cup final was foiled, but the grandstand of the Manor Ground football stadium in Plumstead – then home to Woolwich Arsenal – was attacked, causing £1,000 worth of damage.

Many of these incidents have been forgotten or lost in the annals of time, but one has remained a landmark moment with a tragic ending.

When Emily Davison stepped out in front of the King’s horse at the Epsom Derby in June 1913, it is thought she meant to emblazon the horse with a suffragette banner in order to make a statement and, undoubtedly, the next day’s front page.

Instead, Davison died after being injured by the charging horse.

Queen Mary, sat with the King in the grandstand at Epsom, described Davison as a “horrid woman” in her journal later that evening.

But Davison’s final action paved the way for progress.

Davison visited Wimbledon on the the day before her fateful trip to the Epsom Derby.

The theory runs that she visited fellow suffragette and old friend Rose Lamartine Yates, the dynamic leader of the WSPU’s Wimbledon branch, in order to pick up the ‘Votes for Women’ banners to wave on the course.

Wimbledon, the south-west London suburb, rather than the tennis championships, had become a hotbed of suffragette activity, long before the attack on the All England Club.

Yates defied the authorities’ attempts to outlaw her public appearances by speaking every Sunday on Wimbledon Common, attracting crowds of up to 20,000 people.

One such meeting in March 1913 descended into chaos as 300 police officers attempted to prevent the suffragettes from gathering. The following week an anti-suffragette counter-protest used a motor horn and noxious hydrogen sulphide gas to try and disrupt the speakers.

“Many of you seem to think these meetings are prohibited,” Yates told her detractors in April. “But until we are informed of that fact we shall not deprive you of the pleasure of listening to us.”

Yates needed the help of mounted officers and a police cordon to return home as a mob of anti-suffragettes swirled around her.

A local ‘Retaliation League’ vowed that ‘every act of violence perpetrated by these women will be answered by attacks on the private houses or properties of Militant Suffragettes’ while women’s weekly magazine The Gentlewoman branded them “a collection of wildly irresponsible females”.

Winston Churchill, home secretary from between 1910 and 1911, was quoted as describing the suffragettes as “a band of silly, neurotic, hysterical women”.

The police were treating the suffragettes’ campaign as a terrorist enterprise, but were struggling to get it under any kind of control.

They tried desperately to identify and imprison any prominent members of the party who they suspected of carrying out bomb and arson attacks. Some of those who were jailed would go on hunger strike to continue their protest and were force-fed.

Yates herself had served a month in Holloway for obstruction during a suffragette march on Westminster. She hosted events celebrating the release of other prisoners of the cause.

While Wimbledon WSPU would still hold summer festivals where hand-knitted children’s clothes were on sale to raise money, the campaign’s more direct action alienated some among the general public.

“The moment you target ordinary people and disrupt ordinary people’s lives, support is lost,” said Dr Riddell.

“The moment the suffragettes begin bombing train carriages and sporting venues and public places that people would go and expect to enjoy time with their family, the public support becomes weaker.”

But the suffragette message remained clear: ‘No peace until women get the vote’.

Back to that night at the All England Club in February 1913 and the woman preparing to burn down one of the Centre Court stands – was she successful?

In short, no.

The groundsman, Joseph Parsons, found the woman and, after she attempted to run away but fell over, caught her and reported her to the police before any damage was done. The attack was foiled.

The unknown suffragette spoke only once, when charged at the police station to say “I object to being charged. I object to being detained here.”

She appeared in court, giving no details of herself – no name, age or place of birth. Her identity remains unknown.

The woman, who newspapers at the time estimated to be around 35, was sentenced to two months in prison – a damning statement from Parsons enough to seal her fate.

Her silence in court led some newspapers to dub her “the silent suffragette”.

Surely, someone knew who she was. Someone like Yates.

“If Rose was not carrying those acts out herself, she would certainly be aware of who was being sent by the leadership of the WSPU into her territory to carry out these attacks,” said Dr Riddell.

“Or it would have been someone that she would have personally known.”

The identity of the mysterious suffragette will likely never be known, but her plot to set fire to Wimbledon was one incident in a vast operation which spanned many years and dominated discussion.

Eventually, World War I broke out and the bombing campaign was put on hold, much to the dismay of some members of the WSPU, including Yates.

But the suffragettes wanted to show that they could be reasonable and helpful, contributing to the war effort as an evolving strategy in the fight against inequality.

Women over the age of 30 were given the right to vote after the war in 1918, but it wasn’t until 1928 that British women won suffrage on the same terms as men, that is, for ages 21 and older.

“The reason women have the vote today is partially because of the bombs,” said Dr Riddell.

“When World War I ends there is a very clear risk that the suffragettes will start their bombing campaign again and the government and the Metropolitan Police, who have been unable to break apart the bombing campaign, can’t understand who is making the explosives and where they’re coming from.

“They’re unable to cope, they’re terrified that the bombing is going to start again in a society that has been completely traumatised by war.

“I don’t think we would have got the vote without the bombs, without the outbreak of war and the threat of the bombs coming back.”

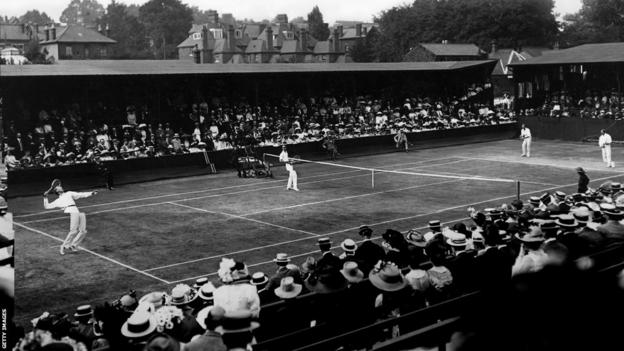

Shortly after the war, the All England Club also implemented some changes, moving from its Worple Road site to the one it occupies today on Church Road. Larger crowds were the reason behind the relocation. And one of the main draws at the tournament was Frenchwoman Suzanne Lenglen, the first women’s world number one, a six-time Wimbledon singles champion and perhaps the first female sporting superstar.

Progress on Centre Court and off. The silent suffragette may not have succeeded on that February night in 1913. She was on the wrong side of the law, but she proved to be on the right side of history.