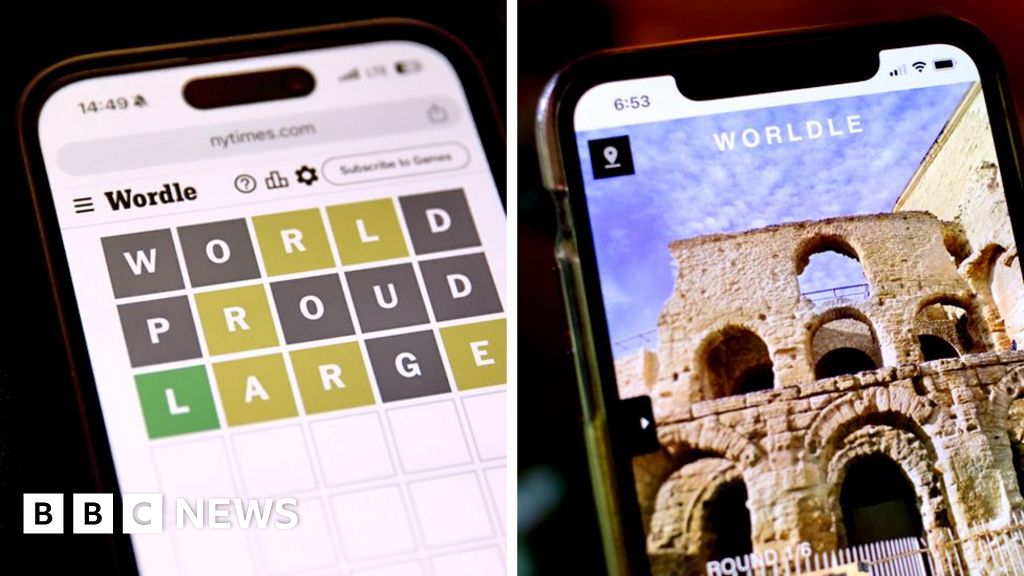

The owner of the hit online game Wordle is legally challenging a geography-based spinoff called Worldle.

In the filing, the New York Times, which purchased Wordle for a seven figure sum in 2022, accuses its near-namesake of “creating confusion” and attempting to capitalise on “the enormous goodwill” associated with its own brand.

But the creator of Worldle, software developer Kory McDonald, is vowing to fight back on the grounds that there are many other games with similar titles.

“There’s a whole industry of [dot]LE games,” he told the BBC.

“Wordle is about words, Worldle is about the world, Flaggle is about flags,” he pointed out.

The New York Times disagrees.

Worldle is “nearly identical in appearance, sound, meaning, and imparts the same commercial impression to… Wordle,” it says in its legal document.

The paper told the BBC it had no further comment to make beyond the contents of its legal submission.

British inventor Josh Wardle developed Wordle in 2021 as a side project to keep his girlfriend entertained.

But since then it has become a behemoth, reaching millions of people worldwide.

By contrast, around 100,000 people play Worldle every month, according to Mr McDonald, who is based in Seattle.

It is not available as an app and can only be played via a web browser.

It contains ads, with an option to play ad-free for £10 per year but Mr McDonald says that most of the money he makes from the game goes to Google because he uses Google Street View images, which players have to try to identify.

He chooses a different one himself every evening for a new game the following day.

“It’s pretty humbling to think that so many people play every month,” he said.

“I didn’t expect it to have this sort of success at all.”

He is not the only one riding on the coat-tails of Wordle’s success. Others include:

- Quordle, a set of four words to guess at the same time

- Nerdle, a maths-based challenge

- Heardle, which is based on identifying music

There’s even another game called Worldle, which involves identifying countries by their outlines.

The New York Times declined to say whether it intended to pursue them as well.

Speaking to the BBC last year, its head of games, Jonathan Knight, said imitation was “the best form of flattery”.

“We’ve always been fine with [similar games] and think that they just help keep the game fresh and alive for people,” he said then.

This is not, though, the first time the New York Times has resorted to the courts to protect its prize game.

In March 2024, a Shetland dialect version of Wordle said it would be shutting down following a copyright challenge from the publishing group.

Prof David Levine, a copyright expert at Elon University School of Law, suggested the writing might be on the wall for Mr McDonald’s project too.

He said the one-letter difference between the two names was potentially problematic, and added there were also “other aspects of likely consumer confusion”.

“You’ve got the pronunciation,” he told the BBC.

“I mean, I I have to make an effort here to say Wordle versus Worldle.”

Mr McDonald said he was disappointed legal action was being taken against him, but insisted he was undaunted.

“I’m just a one-man operation here, so I was kinda surprised,” he said.

“Worst-case scenario, we’ll change the name, but I think we’ll be okay.”

Additional reporting by Franchesca Hashemi