Herndon was hardly alone in his attachment. Bomb-disposal robots have proven to be highly effective both at clearing explosives and at eliciting affection from their human handlers, some of whom have held robot funerals and award ceremonies for favoured bots.

These relationships offer illuminating insights into the experience of working with a robotic teammate, something an increasing number of workers in fields from healthcare to retail will be called on to do.

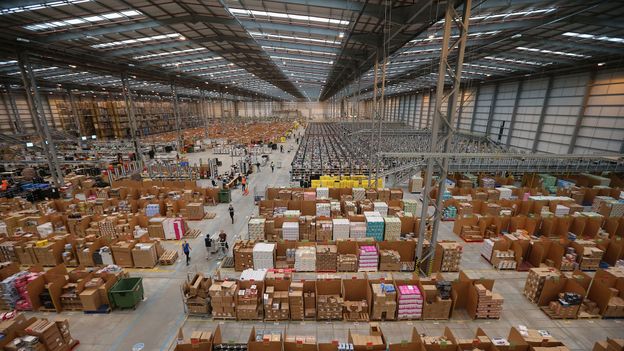

Industrial robot installations worldwide have grown an average of 12% each year since 2013, according to the International Federation of Robotics. North American companies took in a record number of new robots in 2018, with shipments of non-automotive workplace robots rising 41% from the year before, according to the Robotics Industries Association.

The proliferation of robot coworkers has prompted psychologists, roboticists and managers in a variety of fields to explore what makes for a successful robot-human collaboration, and what makes these relationships go awry.

‘Helping, not taking jobs’

“You need to think from the beginning of how you’re going to put these teams together, and give the robot [or] AI the job that the robot or AI does best and that the human doesn’t want to do, or that’s too boring or dangerous for the human,” says Nancy Cooke, a professor of cognitive science and director of Arizona State University’s Center for Human, Artificial Intelligence, and Robot Teaming.

Workers seem to find robots most useful and respond best to their introduction in the workplace when they are integrated as a complement, and not a replacement, for human labour.

Nicole Burke joined the US grocery chain Stop & Shop in 2001 as a 16-year-old cashier in Aberdeen, New Jersey. After working her way up through the company, she is now a liaison between the chain’s stores and corporate offices.