When Didier Deschamps leads his France side out to face England in their World Cup quarter-final on Saturday, he will be hoping to take a further big step towards becoming only the second manager to retain the trophy.

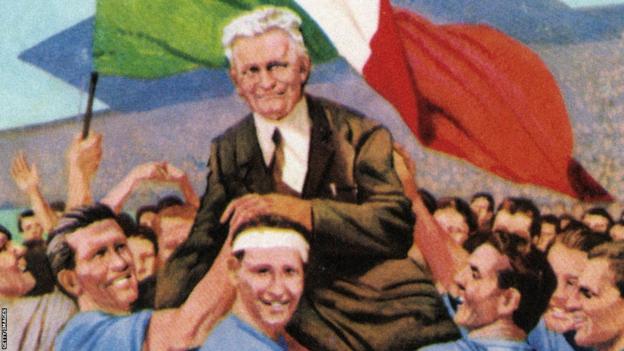

Just two nations have managed to win back-to-back men’s World Cups, Italy in 1934 and 1938 and Brazil in 1958 and 1962, but with the Selecao job changing hands between successes, former Azzurri coach Vittorio Pozzo stands alone.

Nicknamed Il Vecchio Maestro (the Old Master) in coaching circles, Pozzo was considered a visionary of the time and is credited as one of the minds behind the Metodo formation, the earliest example of the 4-3-3 we recognise today.

Yet far from being revered as the only manager to win the men’s World Cup twice, Pozzo remains relatively little known. And there is a reason for that.

“It’s deliberate that few people know who he is,” says historian Dr Alex Alexandrou, the chair and co-founder of the Football and War network.

“If you think about post-1945 Italy, and how Fifa and the Italian Football Federation project and promote themselves, the one thing they didn’t want to do was give credence to Pozzo and what happened during the 1930s, because there is a significant link with the far right and fascism.”

Despite Pozzo first taking charge of the national team for the 1912 Olympics – before fascists rose to power in Italy – and never being a member of the National Fascist Party, his story is inextricably linked to the far right movement that culminated in Benito Mussolini’s dictatorship.

The four stars proudly emblazoned on Italy’s national team shirt to symbolise their quartet of World Cup wins acknowledge the victories of 1934 and 1938, but there’s still some unease around them.

“There’s this slight sort of smell, if you like, after the war, and Pozzo isn’t as famous or exulted as he might be because he won his trophies under a fascist regime,” explains Italian football expert John Foot in new book How to Win the World Cup.

“He wasn’t forced to do that; he participated in that. The players gave the fascist salute and there was a lot of rhetoric around them, so it’s a problem in terms of Italy. Do those World Cups even count?”

Sport historian Prof Jean Williams adds: “A lot of people describe Pozzo as capitulating to the regime – he goes along with it rather than standing up to it.

“Unless you were going to leave the country, it was very difficult to avoid, in the same way that a lot of young men would have become part of the Hitler Youth [in Nazi Germany] because it was essentially their version of the boy scouts.”

Dr Alexandrou agrees: “I don’t think Pozzo had much time for politics per se or even for the fascists, but he loved his football and he had to survive in that regime. He did what he felt he had to do in order to do the job he wanted to do, which was to manage.”

Mussolini’s fascist government had quickly identified the value of a strong association with football after seizing power in 1922 and its involvement with Italy’s national game deepened as the country became a dictatorship.

Money was poured into the sport in search of the best possible chance of success on the international stage, with Serie A reorganised in 1929 to create stronger competition and help develop players that could compete at the top level.

Militia general Giorgio Vaccaro was installed as the head of the Italian Football Federation. But when it came to the national team, Pozzo was the poster boy.

Italy were World Cup hosts in 1934. The country’s rulers considered it crucial that they win, thereby reaffirming fascism’s strong nationalist values and conveying the image of a modern and assertive nation to the rest of the globe.

Although a combination of Pozzo’s tactical approach and a partisan home crowd would help Italy’s chances of glory, there were also rumours of foul play – with Mussolini allegedly meeting with tournament referees the night before key matches.

Although no corruption was ever proved, opponents complained of officials’ leniency towards the Azzurri’s physicality. Swiss referee Rene Mercet was even suspended by his own football association following claims he made several controversial decisions as Italy squeezed past Spain in a heated quarter-final replay.

Despite the accusations, there was no doubt Pozzo’s tactical ingenuity had an impact. The Italians conceded only three times in five matches – particularly impressive given the comparatively free-scoring nature of the time. The coach’s preference for playing with four defenders and a holding midfielder gave them a stronger footing in the face of the popular 2-3-5 formation.

“We start to see the beginnings of the catenaccio defence where the centre-half is a kind of stopper,” Williams explains.

“Under Pozzo, instead of a centre-half being the one that spread the ball around, the midfield became more important, with a holding midfielder and an attacking midfielder, or inside rights and lefts, as they were called in those days.”

Pozzo can in another sense be seen as a forefather to the modern international manager in his insistence on having full control over team selection. Previously many national sides were chosen by appointed committees, but Pozzo said the best chance of success was for the coach to take responsibility – something Sir Alf Ramsey also did upon becoming England manager in 1963.

This meant Pozzo could call upon the oriundi, a term used to describe foreign-born people with Italian descent, to bolster his side’s ranks. Within that diaspora, he called up Luis Monti, who had played in the 1930 World Cup final for Argentina, and Raimundo Orsi, another former Argentina player who would score for Italy in the 1934 final, a 2-1 victory over Czechoslovakia.

This wasn’t universally popular among the fascist regime, but the prospect of forming a stronger national side tipped the debate in Pozzo’s favour. His new-look side were well organised, treated matches like battles and would stop at nothing to win. Training camps were punctuated with strong nationalistic messages and the squad treated almost as if they were soldiers, with exercises such as marches through the woods commonplace.

Pozzo continued to develop his approach in the ensuing four years, leading Italy to victory at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin and becoming the first manager to win a World Cup on foreign soil in France in 1938.

Facing a vocal anti-Italian crowd in their opening match of the tournament against Norway in Marseille, Pozzo and his players held a fascist salute as an act of defiance and refused to lower their arms until the jeers died down. Upon lowering their salute the noise began again, with Pozzo barking the order to raise their arms once more.

As Italy progressed through the tournament, a quarter-final meeting with hosts France only further dialled up the political tension and a kit clash saw the Azzurri, changed from their usual blue shirts, opting to play in all black rather than their second colour, white, on orders from above.

By now Italy carried a little more creativity to go with their clout, with Giuseppe Meazza growing in influence in the centre of Pozzo’s carefully constructed midfield. The captain was instrumental as the holders dispatched France 3-1; he then scored the winner from the penalty spot against Brazil in the semi-final; and in the final he teed up Luigi Colaussi and Silvio Piola as the forwards scored twice each in a 4-2 win over Hungary.

The significance of a second consecutive World Cup victory wasn’t lost on the fascist government back home, with a myth emerging that Mussolini sent a telegram to the team on the eve of the final saying “win or die”. It’s a detail that has never been confirmed.

But it would prove to be the end of Pozzo’s World Cup story. The outbreak of the World War Two meant the tournament didn’t return until 1950, by which time he had been relieved of his duties and banned from Italian football because of his association with the now-overthrown fascist government.

Pozzo went on to become a well-respected journalist covering the Italian national team for daily newspaper La Stampa, but he would never return to the dugout. He died in December 1968, aged 82.

“Pozzo was obviously a very good leader and very good at mobilising and motivating his teams,” Foot continues in How to Win the World Cup.

“He saw football as war and used national rhetoric around international tournaments. It was like war had been transported onto the pitch.”

Chris Evans is the author of How to Win the World Cup: Secrets and Insights from International Football’s Top Managers